Professor Siedlecki awarded tenure and promotion to Associate Professor

Congratulations to Professor Samantha Siedlecki who was recently awarded tenure and promotion to Associate Professor from the University of Connecticut! We are so proud to have Prof. Siedlecki as a member of our department and to see her awarded tenure.

Professor Siedlecki has been a highly valued member of our department since her arrival at UConn in 2017 and has played many leadership roles in our department and the broader scientific community. Dr. Siedlecki’s research group focuses on coastal biogeochemistry using a combination of simulations and observations to characterize historical and ongoing change and forecast future trends. A particular focus of her group’s work is on coastal carbon and oxygen cycling, including the impacts of decreasing ocean pH (ocean acidification) and decreasing oxygen (deoxygenation) resulting from climate change and other human impacts.

Her research accomplishments have been recognized through an Early Career Faculty Innovators Program Fellowship from NCAR and a Kavli Fellowship from the US National Academy of Sciences. Since her arrival at UConn, she has received approximately 16 grants totalling over $4 million in funding from organizations including NOAA and NSF, including serving as co-lead PI on a $1 million grant on assessing the vulnerability of sea scallops to ongoing ocean change.

Her teaching contributions have included developing two new courses, Ocean Expedition (a very popular course for our graduate students) and Biogeochemical Modeling, and teaching Environmental Reaction and Transport, a course that allows undergraduate students to develop their quantitative and problem solving skills. She has mentored numerous personnel in the department, and currently supervises two PhD students, one masters student, one research associate, one research scientist, and multiple undergraduate students.

Dr. Siedlecki has been highly active in departmental service, having served on several departmental committees, including the Advisory Committee to the Head, and was a founding member of the department’s Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion committee. She was recognized with a Climate, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Award from the UConn College of Liberal Arts and Sciences in 2022 due to her contributions to fostering an inclusive climate in our department and at UConn.

Outside of UConn, she has had substantial contributions to research organizations and activities at the regional, national and international level, including serving as co-coordinator for the Northeast Coastal Acidification Network (NECAN) and serving as a member of the international scientific committee for the 5th International Symposium on Oceans in a High CO2 World, and also gave an invited plenary presentation at this conference. Dr. Siedlecki makes stakeholder engagement and outreach critical components of her research program and has participated in numerous outreach activities with members of the aquaculture industry and management organizations along with members of her research group.

Dr. Siedlecki has co-authored approximately 36 publications and some of her recent publications are listed below.

Now that she has been awarded tenure, Prof. Siedlecki looks forward to finalizing her group’s work with east coast coastal communities through a regional vulnerability assessment of scallops and the communities who rely on them. She plans to conduct similar assessments in other regions with the international research community and is currently preparing a proposal with South African colleagues.

Congratulations to Dr. Siedlecki! We are excited to watch the future accomplishments by you and your team!

Recent publications:

“Seasonality and life history complexity determine vulnerability of Dungeness crab to multiple climate stressors” by Berger et al. (2021) in AGU Advances. This paper was led by Siedlecki lab graduate student Halle Berger.

“Coastal processes modify projections of some climate-driven stressors in the California Current System” by Siedlecki et al. (2021) in Biogeosciences.

“Projecting ocean acidification impacts for the Gulf of Maine to 2050: New tools and expectations” by Siedlecki et al. (2021) in Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene.

Prof. Siedlecki at the Avery Point campus

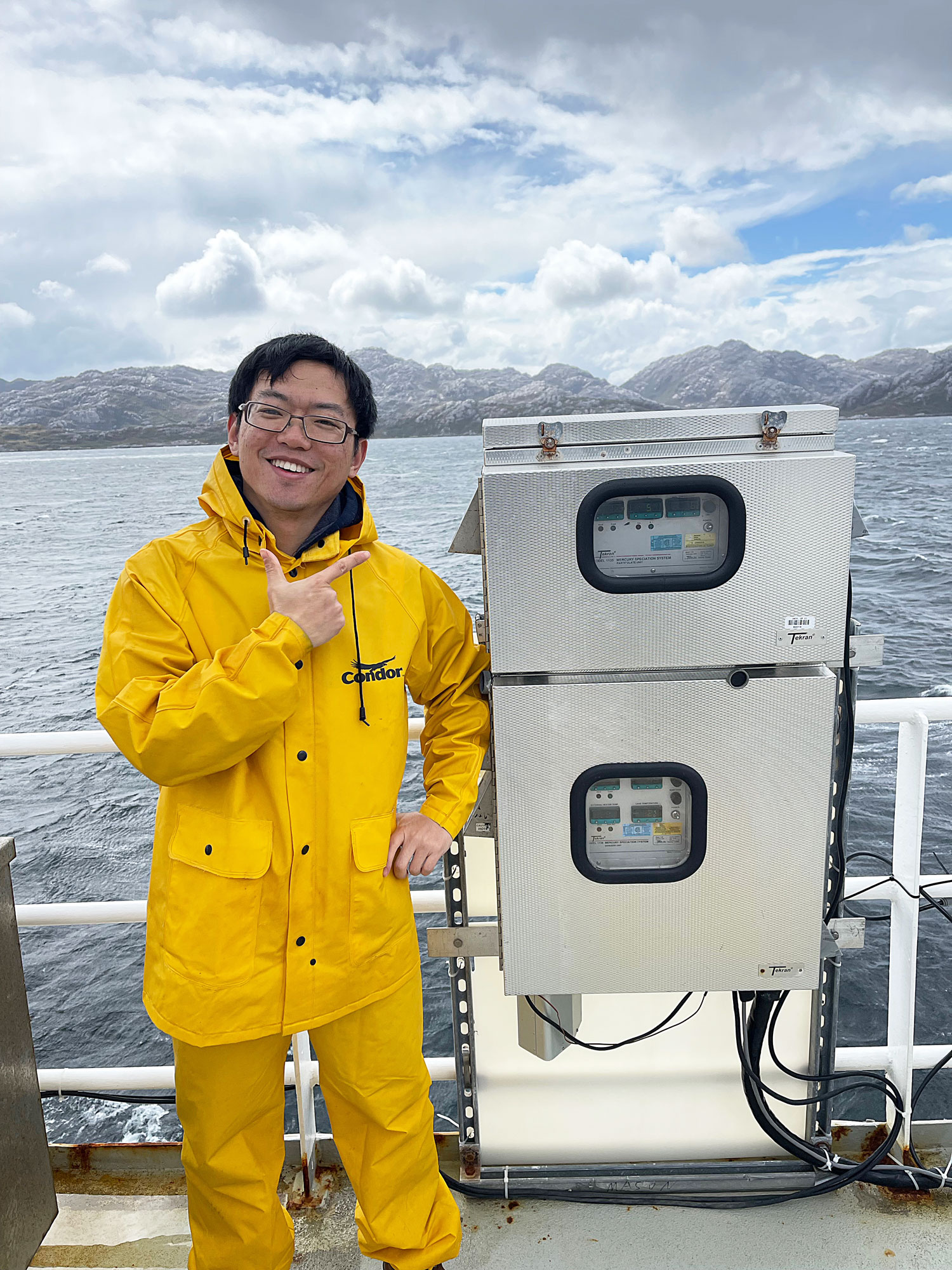

Prof. Siedlecki and PhD student Halle Berger in Norway following a research conference.

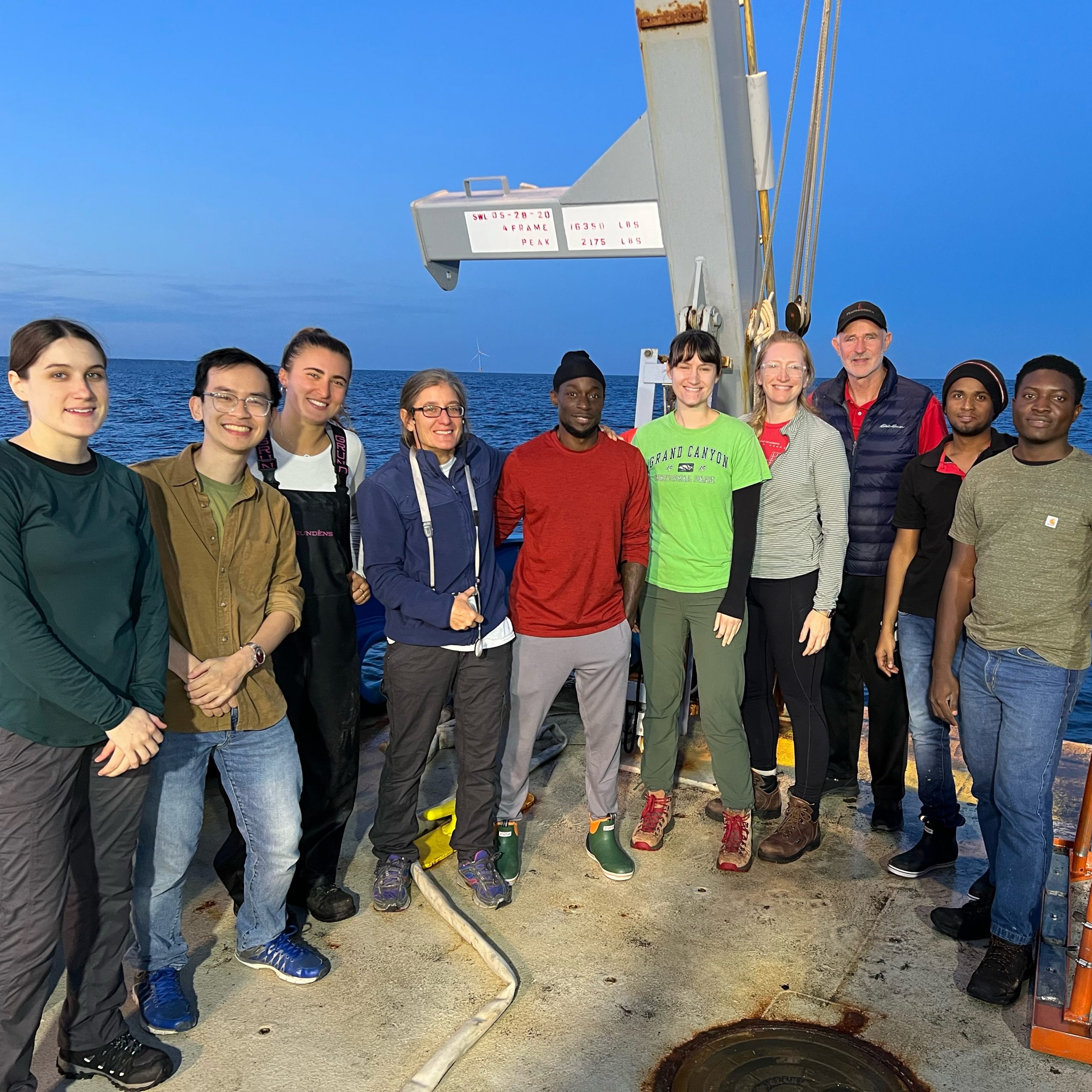

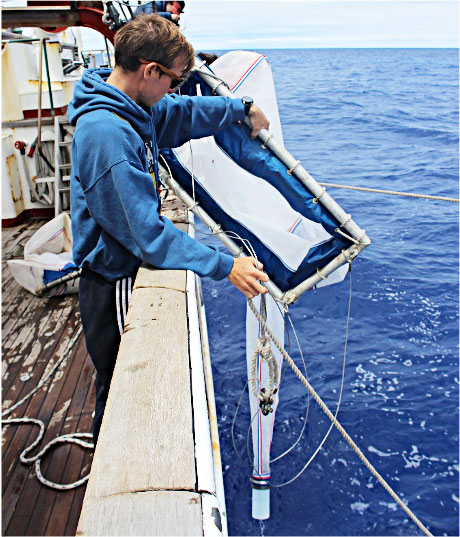

Prof. Siedlecki on the R/V Connecticut during the Oceanographic Expedition graduate course in 2022

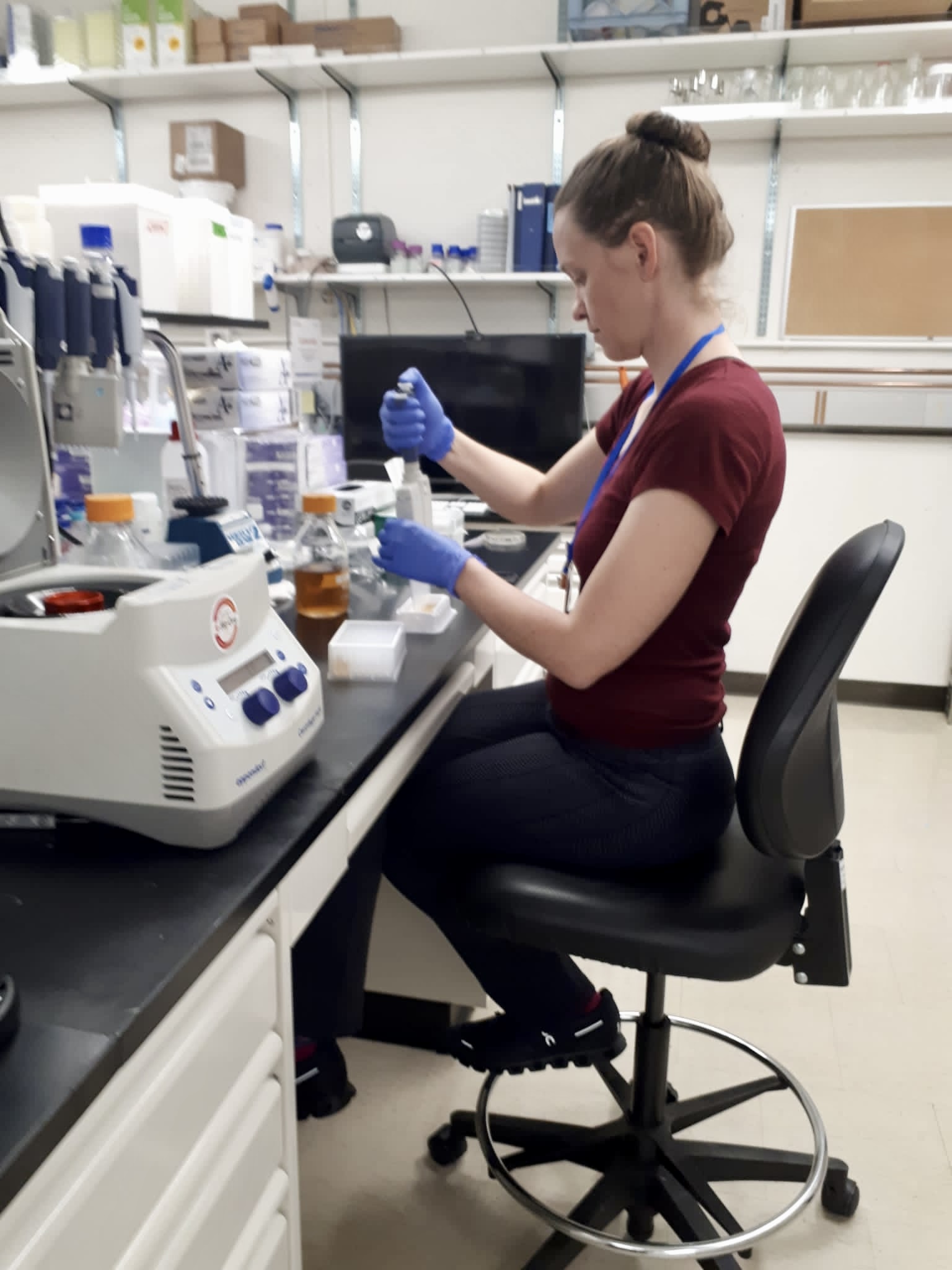

Bridget Holohan – MVP technician

Graduated Master and PhD students 2022-23

CT-NERR is fully staffed and operational!

Brittany Sprecher continues science in Germany and California

Finally in person again: Feng Graduate Research Colloquium 2023!

Our [student] Life on the Ocean

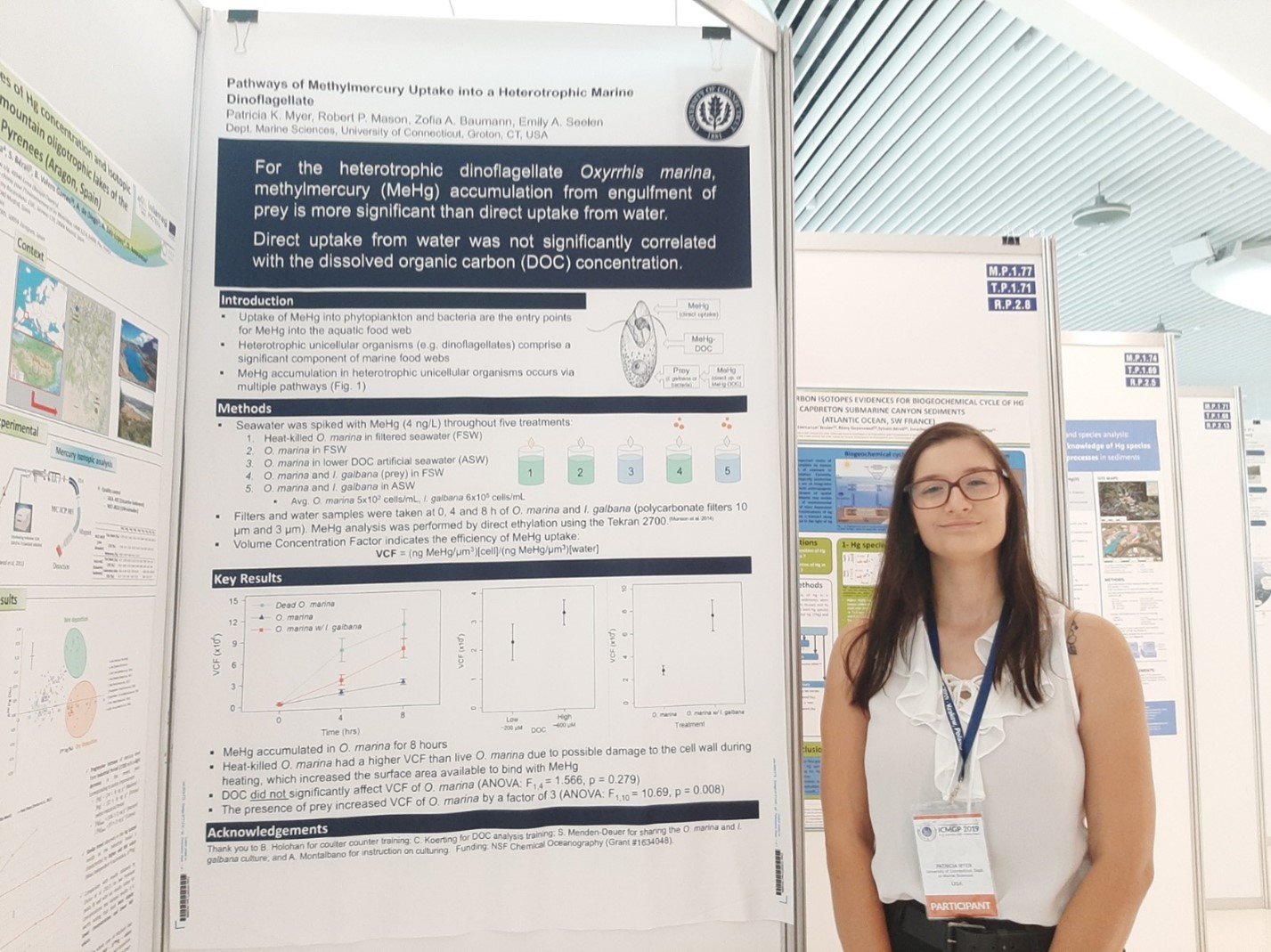

Congratulations to Dr. Patricia Myer, PhD!

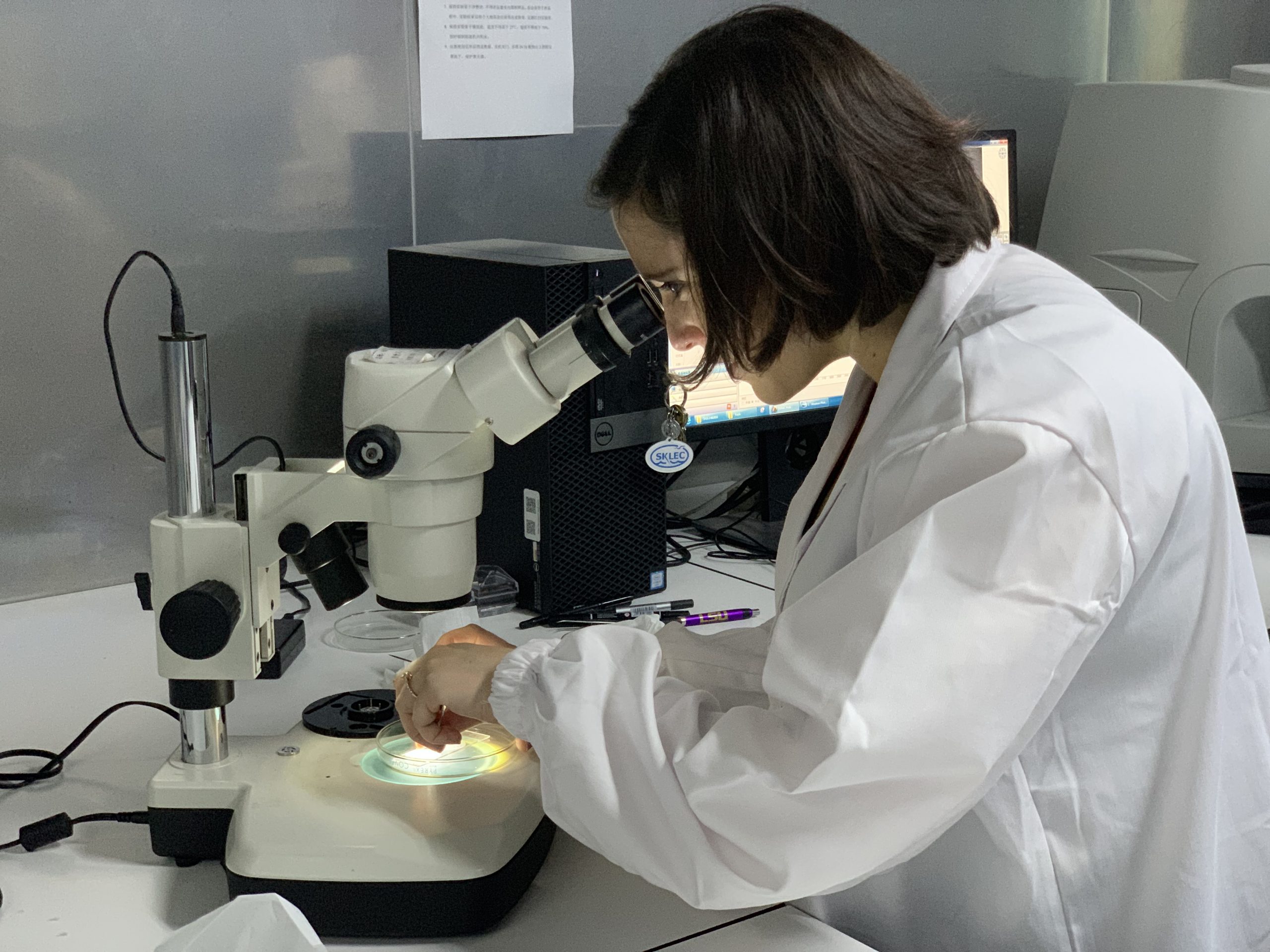

Congratulations to Dr. Patricia Myer, the department’s newest PhD! Here is a description and some photos of Dr. Myer’s PhD journey, in her own words.

My Ph.D. dissertation defense was on March 20th, 2023, and titled “A Critical Examination of the Factors Controlling Methylmercury Uptake into Marine Plankton.”

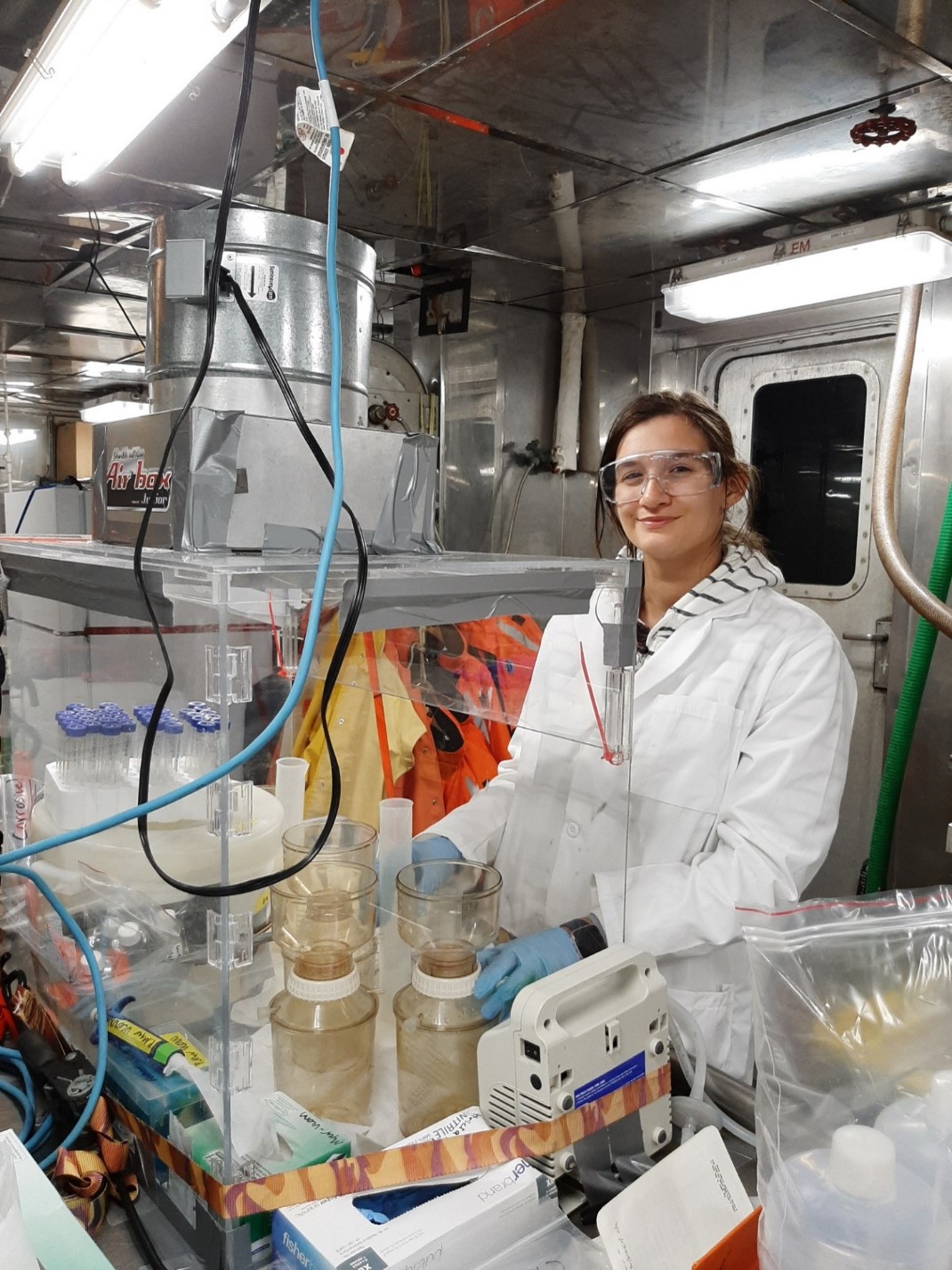

I am a student in Dr. Robert Mason’s group and my research includes a three-year long time series of methylmercury in phytoplankton in Narragansett Bay, RI, a research cruise in the Northwest Pacific (NOAA GU1905), and laboratory uptake experiments with the dinoflagellate O. marina.

The goal of these projects was ultimately to compare the effects of biological and environmental variables (e.g., cell size, temperature, dissolved organic matter) between laboratory experiments and environmental studies to try to disentangle the leading drivers of methylmercury accumulation into plankton. The main takeaway is that relationships seen in laboratory experiments, both from my work and the literature, are not nearly as straightforward in the environment. There is a lot more work to be done to understand these complex relationships.

Currently, I have one publication from my prior undergraduate work (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-022-02548-0) and one from my work in the Mason lab that is not part of my dissertation (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134609). I am currently preparing three papers relating to my dissertation for publication.

This work was funded by NSF Chemical Oceanography and the UConn Predoctoral Award.

Kayla Mladinich Poole receives R. LeRoy Creswell Award for Outreach and Education