The ole adage holds true for DMS graduate student Emma Siegfried’s first experiments on a new species of sand lance

By Samantha Rush and Hannes Baumann

In 1984, the late Alphonse Smigielski and colleagues published a research paper that showed how American sand lance (Ammodytes americanus) could be successfully spawned and reared in the laboratory. Now, DMS PhD student Emma Siegfried is working to continue experimental research on this species, finding that revisiting the 40 year old study is not without challenges.

Sand lances are so called forage fish, meaning that their role in the ecosystem is to eat tiny planktonic organisms while being important food themselves for higher trophic animals such as other fish, seabirds, and marine mammals. Despite their importance, there is insufficient information about how this species will cope to climate change, particularly during the most sensitive larval and embryo stages. To fill this knowledge gap, Emma’s work focuses on exploring how increasing water temperatures and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels affect sand lance embryos and larvae.

Previous research conducted in Prof. Hannes Baumann’s Evolutionary Fish Ecology lab discovered that embryos of the closely related Northern sand lance (Ammodytes dubius) are extremely sensitive to elevated CO2 levels, as they are projected to occur in future oceans. However, whether American sand lance are equally CO2 sensitive is not known.

Emma’s thesis research began in 2024 by first trying to find a reliable and easy to access location, where the species could be found and collected. In the harbor of the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve in Wells, Maine, she found what she needed, because her fish occurred in high numbers there and could be sampled at low tide easily via beach seine. Now Emma’s goal was to catch the fish as close as possible prior to their spawning season, which in the case of sand lance starts with the beginning of winter.

In late August and early October 2024, Emma and her lab mates successfully collected sand lance and transported them live to the Rankin Seawater at Avery Point. There, however, sand lance proved challenging to care for, as they prefer spending days to weeks burrowed in sand (hence their name), making it difficult to monitor their health and development. Subsequent sampling efforts in November and early December brought a new set back, because the previously accessible population in Wells Harbor had evidently moved into slightly deeper waters and thereby out of reach for the beach seine. Unfazed, Emma proceeded to rear the fish she already had in the lab, hoping that they would ripen and eventually produce embryos for a CO2-sensitivity experiment.

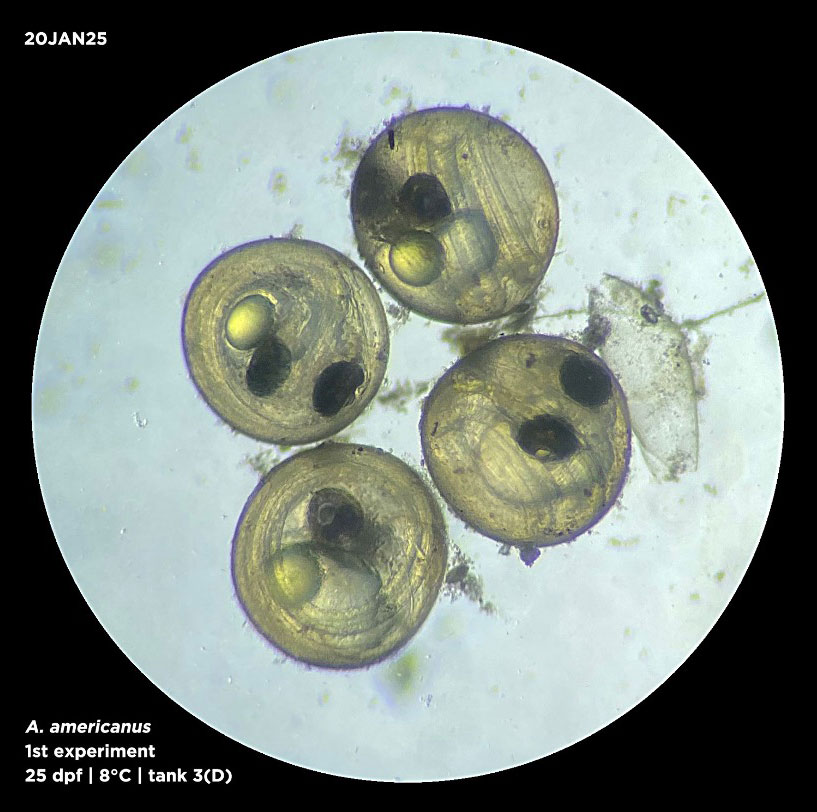

At first, this looked like another failure. Sand lance use the declining temperature as a cue to ripen, but the waters of eastern Long Island Sound that flow through the Rankin lab remained unseasonably warm well into December. Eventually, however, on 23 December 2024, water temperatures crossed the critical 7°C threshold, and 3 days later, Emma and her lab mates indeed succeeded in strip-spawning a few ripened up females! The fertilized embryos were then placed in the Automatic Larval Fish Rearing System (ALFiRiS) that allows computer-controlled exposure of organisms to different temperature and CO2 conditions.

Unfortunately, more experimental setbacks followed. Less than 1% of the embryos actually developed to hatch, the CO2-induced acidification did not produce the desired target pH levels, and a system malfunction remained undetected long enough to raise water temperatures to unnatural levels. Emma remains positive, however, and looks at her trials and tribulations as well as the preliminary data as a valuable exercise in gathering experience with this new, non-model species.

“Even though it didn’t go the way we expected, [we] still learned a lot.” she says.

She added that science is by definition challenging, but she is eager to apply what she has learned and move forward. More generally, her thesis research aims to answer the question whether CO2-sensitivity is a shared trait among sand lance species. To that end, she is applying for a grant to collaborate with researchers in Bergen, Norway who have experience with another, closely related sand lance species (Lesser sand eel, Ammodytes marinus). She hopes to secure funding to travel and conduct research there from December 2025 through March 2026.