By Ewaldo Leitao

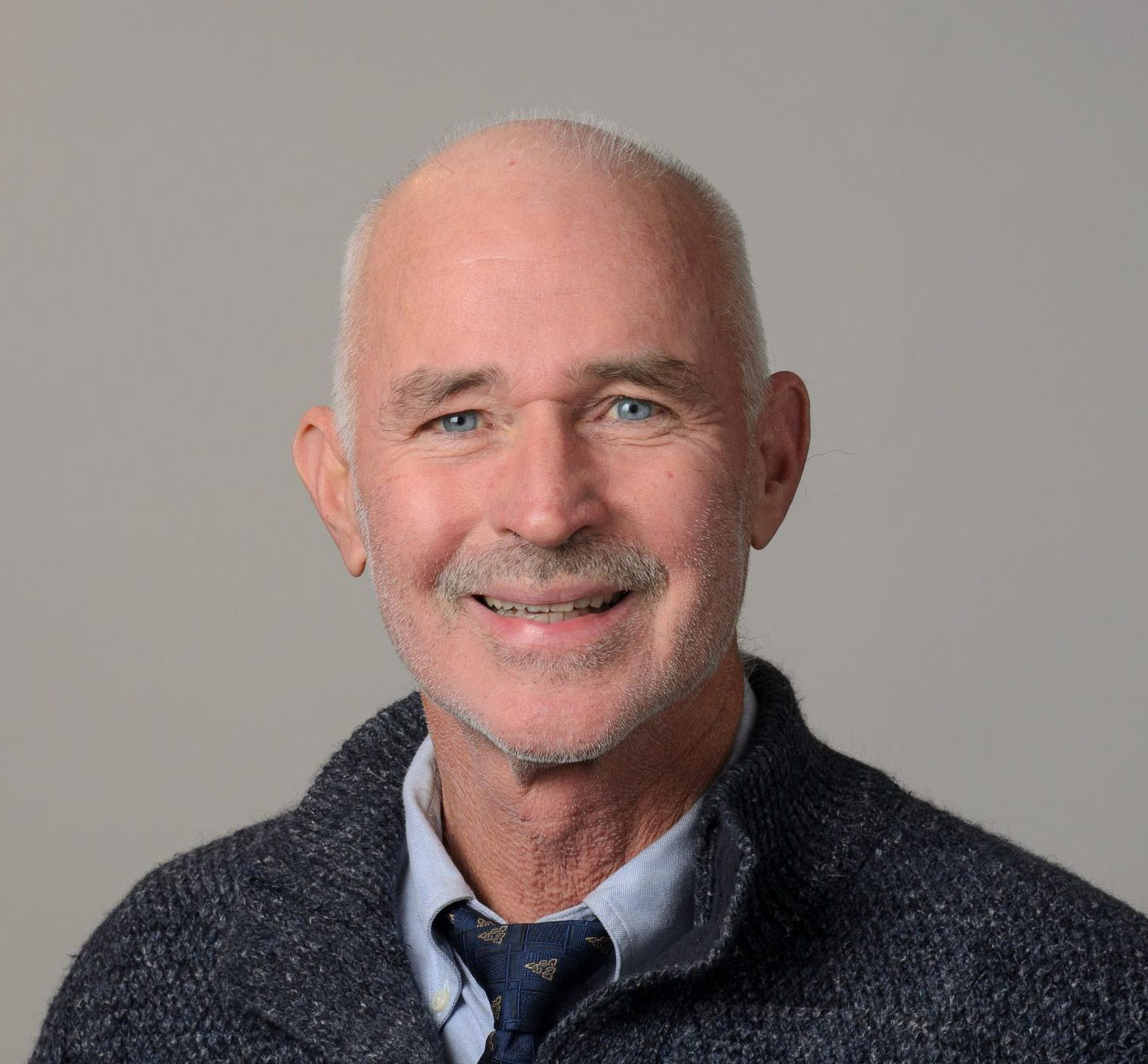

Easy and hard to find – her door is always open but without a name tag – ready to help, and to give advice (for 5 cents), Bridget Holohan has been in the marine sciences community for over two decades. Bridget is currently working for two labs helping in many projects. Bridget is always ready with a sharp, witty joke, which is always appreciated and welcomed. Bridget kindly agreed to be interviewed and to tell us more about her path and career.

Ewaldo: What was your academic journey before you got here?

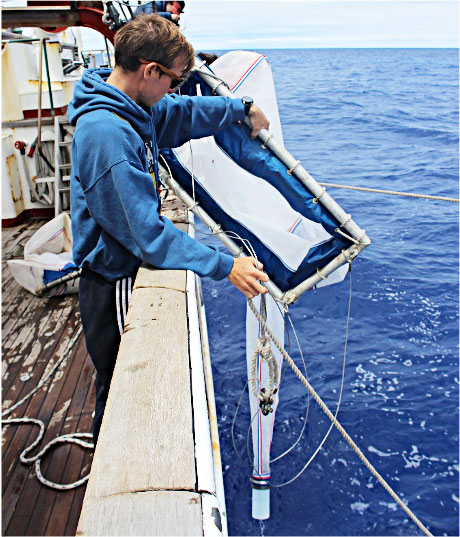

Bridget: I grew up in Michigan, and I wanted to be an oceanographer. The only school close to where I grew up that had an oceanography program was the University of Michigan, and I wasn't quite ready to go across the country at 18. When I was finishing up there –this was before the internet so finding a job to apply for was harder than it is now–I didn't quite know what I was going to do for a job and decided to go to graduate school. Okay, maybe it wasn’t the best decision to go based on that. I went to the University of Rhode Island and got my master's degree. I thought about whether I wanted my PhD, but I decided that I like to be the one getting my hands dirty, not the one writing a proposal or writing the paper. I wanted to be the one doing it. So, I decided if I got a PhD, more than likely, that wouldn't be what I was doing. I stopped at a master’s degree, which was a good decision for me. As I was finishing up there, I saw a job in the state of Connecticut at the Williams Mystic program. They were looking for a TA.

Ewaldo: And how did you decide to be an oceanographer?

Bridget: I decided to become an oceanographer when I was the age of 12. My family went on a cruise down in the Caribbean and one of the things we did was snorkel. The first time I went snorkeling, I was blown away. I had no idea that there were all these amazing things under the surface of the water. No idea. I grew up in the Midwest. I knew about fish, we have the Great Lakes, but the organisms under the water in the Great Lakes do not look like in the tropics. It was just so incredibly fascinating. I wanted to study the ocean but at that point it was just a fantasy doing research on the ocean. I was planning to become a pharmacist because that seemed more sensible. However, when I started thinking about applying to colleges, I asked myself: why would I be a pharmacist? What I really want to do is oceanography.

Ewaldo: Williams-Mystic program. What is it?

Bridget: It's an off-campus study program of Williams College, which is conducted at Mystic Seaport. And it's entirely based around the ocean. Students come in for one semester. It's like a semester abroad, only it is a domestic program which is focused on the ocean. And they take either marine biology or oceanography. They also take maritime history, marine literature, and marine policy. They read Moby Dick, as you might imagine. They totally get immersed in the program.

Ewaldo: That’s super interesting. What was your master’s degree in?

Bridget: My master's research was on the ecology of Ceriantheopsis americanus, which is a burrowing mud anemone.

Ewaldo: And why didn't you follow up on that particular topic?

Bridget: There's not a lot of jobs for that particular topic. So, I found a job that was mainly education. But it was a horrible salary. Like a third of what you students make. So, in the summer, I went to an oceanography summer camp and worked there. Then after a couple of years, I was like: “Okay, I cannot make a living at this”. I was searching around not being so successful. In the meantime, I did another environmental education job down in Virginia, which was fun.

Ewaldo: All the way down! So when did you come back up to the Northeast?

Bridget: As I was finishing that up, my former boss said: “I got a Pew Foundation Grant, and I put in money for a research assistant. Do you want to come work with me?” I said yes and I went to work with him, but it was only a two-year grant. As that was coming to an end, I saw a job by a man named Evan Ward. I didn't really know anything about culturing phytoplankton, which was what he wanted. But I figured I could learn. Why not? Right. So yeah, that's how I got here. And that was in 1999.

Ewaldo: It's been 24 years! And what was your position then – and currently?

Bridget: I was a research assistant when I started. Now, I'm a research assistant three, but in a lot of ways, my job is very similar. The only thing that has really changed is that as funding got tight, I started to work for Rob Mason as well. I also worked with Claudia for some time, because her job was expanding. I like the fact that there's a lot of variety. I hate being bored.

Ewaldo: You have done a lot of different things and learned a lot of things in this dynamic way. What were your biggest challenges and also biggest joys here?

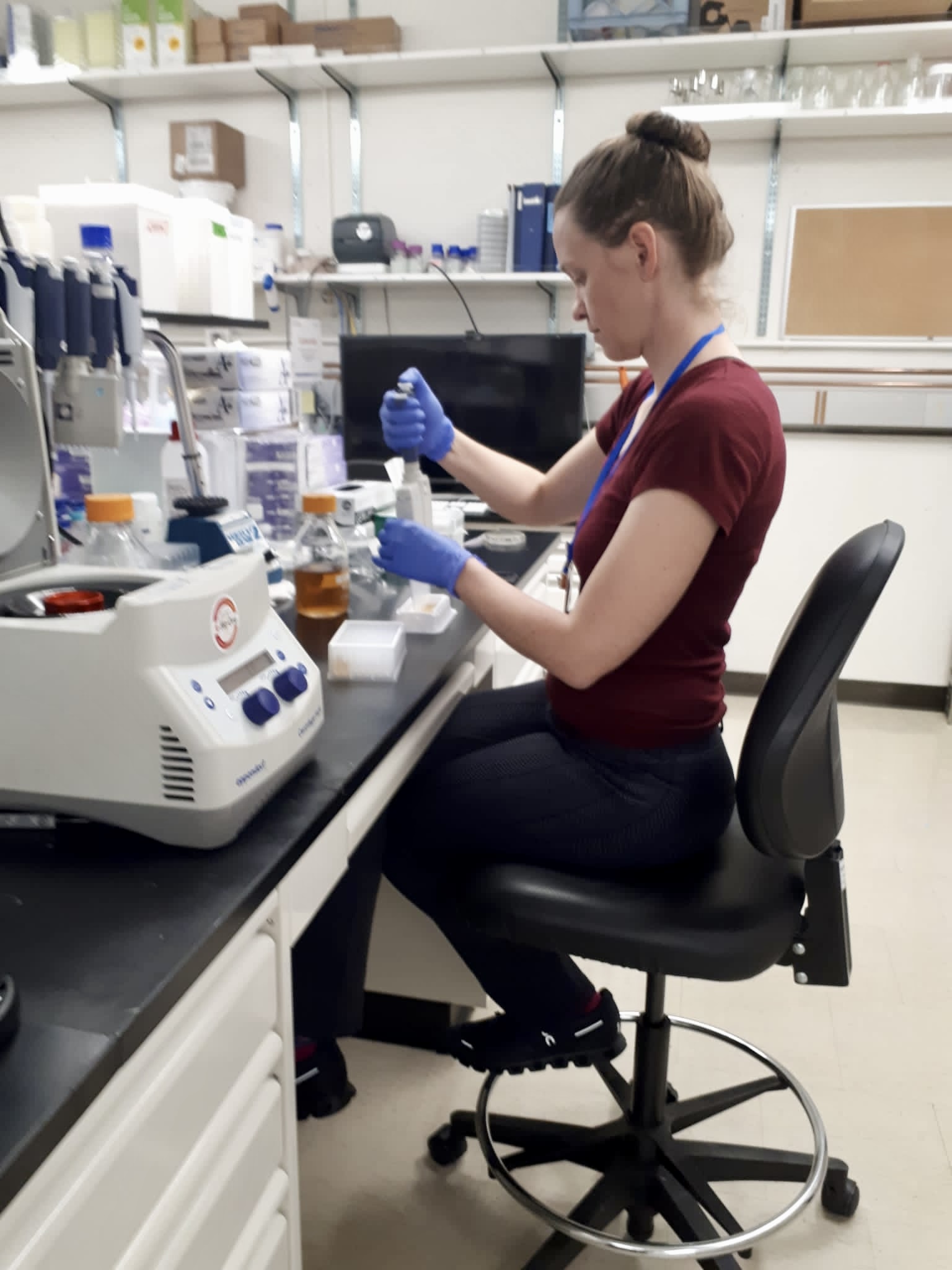

Bridget: You know, I really enjoy working with bivalves, I like running experiments. Even though sometimes they can be a little crazy. I like seeing the whole process, from what we are proposing to do, to making it happen, and analyzing the data. And then luckily, I don't have to write it.

Ewaldo: Would you have advice for grad students?

Bridget: Boy, that's a really good question. One of the things in this is just kind of funny, because writing is not my favorite thing to do. But people often get hung up on the writing portion, thinking to themselves: “Okay, I need to write the perfect sentence”. Sometimes you just need to write. The beauty of the computer is that you can delete it, you can move it, you can copy and paste it into a different document. So you just have to get your ideas down on “paper”, and then refine them later. Just write it down, get it on the computer, and then fix it.

Also, I recognize that there can be a weird power dynamic between students and professors. But with most professors, you can really just say, “I need help with this….” Rather than wasting a bunch of time, being afraid to ask. Professors will be more receptive than if you wait five months and say you haven't been able to get this to work for five months. That is especially true when students are first starting out, and I see that is an easy role for me to fill. Because students are more comfortable coming to me and saying: “Hey, I don't know what's going on here”. Usually I can point them in a direction or even facilitate the conversation. And of course, there have certainly been times that my advice has been about things having nothing to do with oceanography.

Ewaldo: This is all great advice. Thank you. Maybe the final question, what's the story behind the five cents for advice in your door?

Bridget: I came back to my office one day, and we had a new nameplate and my title was wrong. Nobody told us they were going to change nameplates. I was not happy, so I took it off. I, of course, calmed down. I was going to put the correct title and make it more legible by making our names bigger (I shared an office at the time). It wasn’t a priority for me, so I took my time replacing it. One day I came back to my office and the Lucy character from the Peanuts comic was there. In the Peanuts comics, she had a little booth where she gave advice for five cents. One of my colleagues put it in there because sometimes people come to me for things other than science related advice. I found out later that it was Jeff Godfrey. I thought it was super funny, so I just left it. And one day I came back and there was a little bag of nickels.

Ewaldo: Who did that?

Bridget: It was Lydia Norton

Ewaldo: I guess that sounds about right! Hehe. Thank you so much, Bridget!